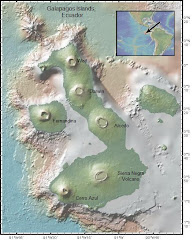

For most of us the introduction to seismic station installation began in earnest at 9:00 am on Thursday, July 23. We loaded the Panga, our launch, as fast and efficiently as possible, while it bobbed in the ocean. No wet feet this time as we jumped out and passed equipment in a chain across pahoehoe. We loaded up quickly and began scouting for a setup location. The sensor had to be in a stable, safe and level position. Without realizing it, we started to settle into what would become our regular jobs. I was a recordkeeper. I used the handheld GPS to mark our landing site, station site and the path in between. I checked off each step of the setup procedure, recorded start up data, kept field notes and used my compass to orient the sensor. Falk became an expert at choosing sites, assembling the solar panel setup and carrying the delicate, heavy sensor. Eliana, and Cindy for the volcano group, were the experienced seismologists and set up experts. For the first two stations, with five of us, the process went smoothly. It took a little over an hour per station and about two hours of sailing time between stations. At GS02 we practiced our barefoot landing skills on a stony beach of rounded basalt pebbles the size of brussel sprouts. My feet were not ready, and I learned that “barefoot landing” meant wear your Tevas. At GS02, the lava was not quite pahoehoe and not quite aa. The flows were broken into large chunks with smooth, ropy tops. It was beautiful. The glassy swirls and bubbles of pahoehoe broke into crinkly spikes, like iguana crests on the edges of the aa-like chunks. Going was tougher, and we learned to wear long sleeves and pants. The importance of carefully choosing a landing site on pahoehoe became clear. Luckily, Captain Lenin understood this as well. With two stations installed, we sailed for Puerto Villamil.

Villamil,Isla Isabela, Galapagos, became the homeport for the Volcano Crew. We assembled in the rain at the Darwin Center office and met Mario Ruiz and Daniel Pacheco, our Ecuadoran colleagues. Then we quickly divided up and went our separate ways. The Boat Crew had six more stations to install, and the Volcano Crew had eight. We had gained Daniel for the boat. Mario headed up the volcano with Cindy and Dennis. Each group faced some uncertainty and risk, traveling by boat, horseback, truck and foot through mud and lava. Aboard Pirata, our first challenge was seasickness (see video).

Each seismic station was different, challenging and beautiful in its own way. We were on an adventure in the Galápagos. At Installation Site GS03, our landing was dependent on the tide. We loaded the panga and surfed through a tiny opening into a cove filled with sea turtles. At GS04, Elizabeth Bay, the panga drifted carefully along a narrow channel to a tiny pool filled with sea lions and sea turtles. On the way out we swam alongside the panga with the sea lions. At GS05, we finished at sunset and faced the possibility of navigating through a lava field with our Petzel headlamps. In near dark, the Panga guided us back just a few feet from rocks covered with penguins, flightless cormorants, sea lions, iguanas and crabs settling down together for the night. They must know they are the tops of the food chain. Fish beware! At dawn we watched the same predators slip off the rocks to find breakfast. GS06 took hours and provided us with an experience that earns a separate description (see Geophysicists and Geologists). But, there was still time to install station GS07 on a narrow arc of pahoehoe surrounded by a sea of treacherous aa, and for some photos of penguins at dusk. On July 27, our panga brought us to Caleta Iguana at the western tip of Cerra Azul Volcano for GS08. Passing a white shrine to the Virgin Mary,we entered another tiny cove filled with sea turtles. Already rain soaked, we climbed and passed from the bobbing panga up, onto a cement dock. The rainy mist, garua, and lack of lava made Caleta Iguana mysterious, as did the poisonous trees. We knew that the biggest trees were the ones we shouldn’t touch. But, surrounded by a jungle of unknown bushes and trees, we were apprehensive. Donning red wool gloves, we scrambled into the mist and pouring rain. We trekked along a tortoise’s trails to locate station GS08. When we encountered him he didn’t seem pleased. We were so wet and busy that we didn’t have time to take a picture of our first wild tortoise, but I later got one of his scat. With the last of our seismic equipment installed, we shooed a sea lion from the dock and returned to the Pirata. It took hours to sail away from the garua and into the sunshine.

The Boat Crew had completed its mission. We had shared experiences and become a team. After a hike up Sierra Negra, Eliana and I returned to our other lives. Falk and Daniel joined the Volcano Crew and had further adventures.